Basketcolor Project: Placemaking, art and play for resilient communities in Juarez, Mexico

“After the first waves of COVID-19, we observed how public spaces (streets, squares, parks) in various cities around the world began to become allies for both economic and sociocultural reactivation. From spaces for outdoor commerce to places of physical activity and recreation, of course, prioritizing the new rules of the game: social distancing, face masks and constant sanitization.” Miguel Mendoza and Nómada Estudio Urbano uses placemaking and a participatory approach to reactivate public space.

“After the first waves of COVID-19, we observed how public spaces (streets, squares, parks) in various cities around the world began to become allies for both economic and sociocultural reactivation. From spaces for outdoor commerce to places of physical activity and recreation, of course, prioritizing the new rules of the game: social distancing, face masks and constant sanitization.” Miguel Mendoza and Nómada Estudio Urbano uses placemaking and a participatory approach to reactivate public space.

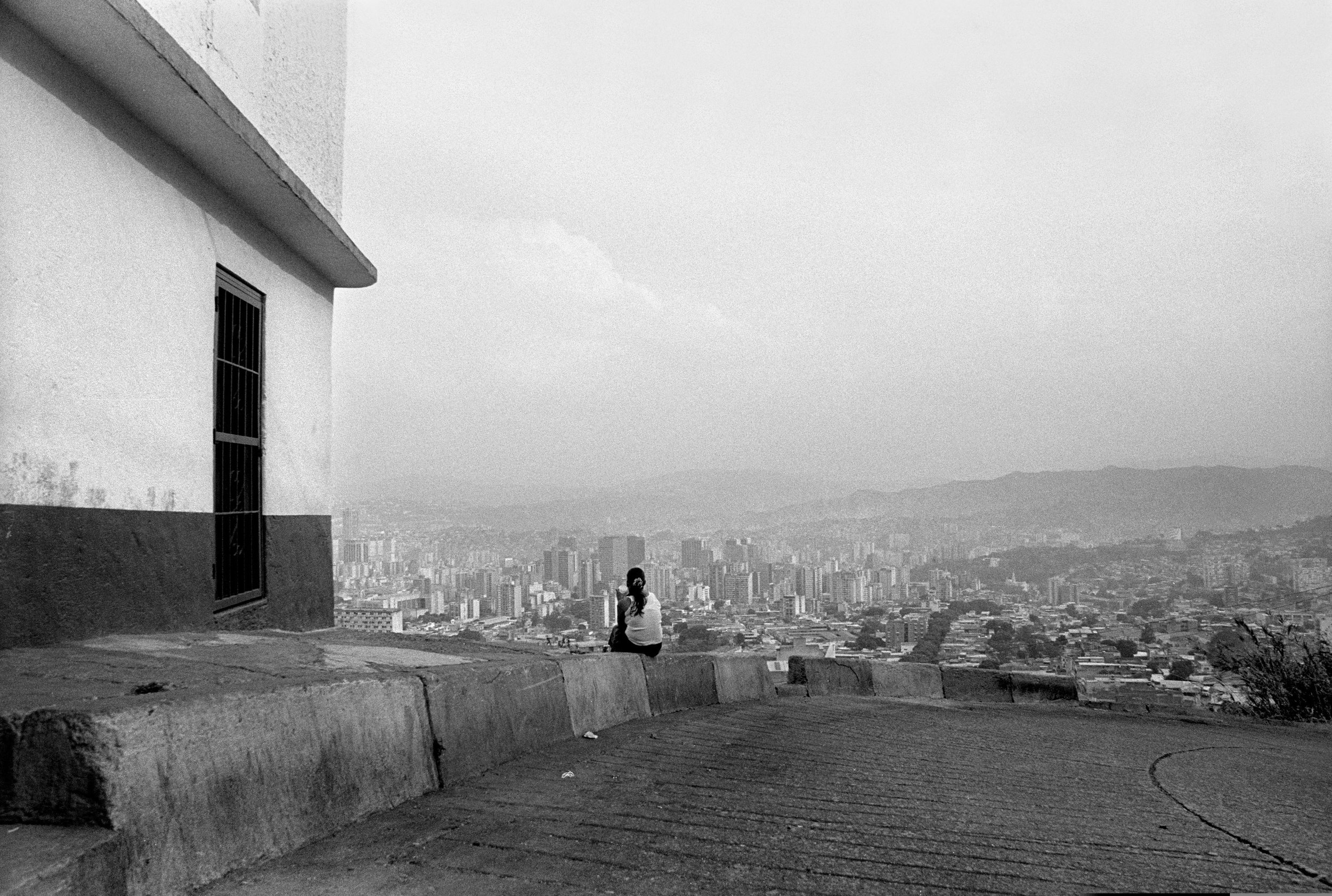

Photo: Miguel Mendoza

As a result of the pause in public life caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, people have had to develop new adaptation mechanisms in the way we approach our cities, communities and, above all, our public spaces.

Nowadays, it is said that we live in a "new normality". However, in a border city as complex as Juarez, Mexico, it is difficult to measure such normality.

For example, in Juarez it was not possible to experience safe confinement in the most critical times of the pandemic. The majority of the population had to be exposed to this new adversity in order not to lose their jobs and remain economically active.

After the first waves of COVID-19, we observed how public spaces (streets, squares, parks) in various cities around the world began to become allies for both economic and sociocultural reactivation. From spaces for outdoor commerce to places of physical activity and recreation, of course, prioritizing the new rules of the game: social distancing, face masks and constant sanitization.

Inspired by these urban adaptations, we began to map spaces in Juarez with the potential to be transformed into multifunctional temporary places for community reactivation processes. That's how we found an interesting common denominator: basketball courts in community parks.

Although Juarez has historically suffered from a deficit of public spaces and the existing parks need to improve their conditions, it is common to find preserved basketball courts in them. In general, the courts in community parks have become bastions of play and one of the most used infrastructures.

Based on these opportunity areas, the Basketcolor Project arose. This project aimed to use placemaking and asphalt art to make basketball courts flexible and adaptable public spaces where play and neighborhood activation coexist.

You may be wondering, "Is it possible to change the traditional context of a basketball court?" The answer is yes, as long as you understand the needs and wishes to be resolved around the space and its users. This is where placemaking and participatory design gain ground.

Photo: Miguel Mendoza

Through placemaking workshops and co-design, we worked with various communities to generate floor mural proposals that could provide the opportunity to also use courts as smart meeting spaces for activities such as flea markets, health fairs, open-air cinema and neighborhood committees. All this, without sacrificing the original purpose for play and recreation.

Throughout the first and second year of the pandemic, the Basketcolor Project allowed the activation of 6 multifunctional basketball courts. As the health situation improved in Juarez and once vaccination was accessible for all, the meaning of the project slowly migrated to the revitalization of courts for recreational use. Now, using placemaking and co-design to consolidate floor murals that make visible the identity and sense of appropriation of the community in which they are located.

Currently, the Basketcolor Project has activated 15 courts in various communities in Juarez and is perceived as a benchmark for citizen participation in the recovery of public spaces. Beyond being an urban art project, Basketcolor is today defined as a community placemaking project that seeks to enhance resilience and generate more humane and playful spaces that reflect the values and uniqueness of the people who inhabit them.

Photo: Miguel Mendoza

Public Space Is a Learning Place

“Any public space is a learning ground. We get to meet strangers and interact with them and learn something from them, we get to experience nature and all its glory and lessons, we get to experience and face different challenges as well.” Peacemakers Pakistani

“Any public space is a learning ground. We get to meet strangers and interact with them and learn something from them, we get to experience nature and all its glory and lessons, we get to experience and face different challenges as well. We get to meet people of different races and backgrounds and share the place with them without feeling any threat, and there's a chance of becoming a friend with them even if it's just a “salam dua friend" meaning someone you just greet on a daily basis.” Peacemakers Pakistani ask us to look around and cherish the shared learning of public space.

Photo: Hari Menon/Unsplash

The behavior of people in public spaces brings to light the issues that the nation or citizens are facing not only on surface level but on a deeper level as well.... If only one has time to focus, observe and analyze. After that when an issue is brought to surface one must try to help solve them in a compassionate manner instead of sitting there and criticize and complain about things. And what one must remember always, the change starts with one human, let that human be you!

So being an observer here is what I have to share with you....

1. We often observe intolerance and impatience in people on road, everyone wants to pass through first, not allowing other person to move ahead or waiting for their own turn. Well, "waiting??", what does that term mean! Unfortunately, we seem to be ignorant of this term. Here in Pakistan, it is sarcastically said "tu lang ja saadi kher" meaning "you can walk over us, we are okay with that". These kind of sarcastic remarks come from deep disappointment I believe and it is becoming our limited belief with time, unconsciously, which is not good. The reason being consumerism culture to me where everything is available at just one click that people have forgotten the habit of waiting for right time and instant gratification being one big disastrous mindset due to that as well. Also, the rat race in which everyone is rushing blindly.

So next time you are outside, observe.... Not only others but yourself as well.... Are you rushing? Are you part of the rat race everyone is? Is it hard for you to wait for your turn? How does it feel in your body? Where can you sense it within you? How is it showing up in your behavior? Then, observe in others, around you, how can you see it happening around you? Is it worth being a part of and keep on practicing daily? If not, what else would you like to practice daily so you may become that human who is tolerant and patient and going with the flow of nature. InshaAllah.

2. People have lost respect for each other including themselves. You can see it in the ways people treat each other on road or any other public space. The way they address each other, the name calling, the harassment cases particularly with girls/women, the bullying with boys, even the abusive behavior and language very frequently seen around. I find some signages and quotations on vehicles as disrespectful and sarcastic as well, there is no need for that but it is frequently seen because sense of humor is being misunderstood and an excuse for disrespect. I wonder why people have forgotten that respect is a fundamental need and moral value of a human being. Allah has given a human being great respect, why people have forgotten their value and position?

So, do you think that those who disrespect strangers would respect those at home? Do you know that the relationship we have with ourselves is what we reflect on the outside with others? How is your relationship with others? How do you treat others? How is your relationship with yourself? How do you treat yourself in times of tension and stress? How do you show yourself self respect? Is it all making sense to you?

3. I see adults (mainly homeless people and drug addicts I am referring to here) showcasing disgusting habits and activities in public and open spaces and living their lives as very discouraging and pitiful state, and then I wonder when I see children around them, (also homeless) not addicts yet but what else would they be if they see no good example around them? Children follow the steps of elders, what are they seeing, what are they copying? Unfortunately I have seen 2 children once mimicking how to smoke hiding from the elders, I have also seen children name calling and harassing girls older than them, I have also seen children laughing at lame jokes just like how elders would with different understanding and intention though, I have seen lot... I wish I was ignorant but I am not....

So what do you think how can this situation be minimized? Do these adults need to be schooled or these kids? What future do you see for them? What might be the cause of their homelessness and drug addiction? What would our kids be learning from them as they see them frequently on roads on daily basis? What mindset and behavior do we need to teach our children towards these people they encounter directly or indirectly? What could be our role as responsible citizens? Do share with me.

4. Leisure, rest and play are rights of all human beings. As we all work daily, either being a student or working person be at home or at office or any profession, the homemakers are included as well... But do we have time and space to rest play and have a leisure time? Is it for free? Are we given the opportunities to enjoy and rest? Are we availing those opportunities? I mainly see people, now, spending their free times in restaurants or in markets.... Consumerism alert! Spending money isn't my kind of rest, play or leisure activity, i mean spending money now would mean me being disturbed to earn money again for more free time or my responsibilities. For me that's double the pressure and stress. Isn't it true? For me, leisure walk on street or in the park that's more relaxing and relieving, the interaction with nature even for few minutes is a source of energy booster but I find it difficult because of the security concerns mainly due to lack of facilities and vehicles on road and yes creepy people lacking mannerism... But, why other people are not outside? I mean if there are more people out for rest and leisure wouldn't it feel secure, the natural surveillance would be such a great support. But do we have time for that, is it a priority for us? Why not? Is rat race and consumerism culture is again a culprit here? What do you think? Do you go out or not? Why yes or no?

5. Any public space a learning ground, we get to meet strangers and interact with them and learn something from them, we get to experience nature and all its glory and lessons, we get to experience and face different challenges as well. We get to meet people of different races and backgrounds and share the place with them without feeling any threat and there's a chance of becoming a friend with them even if it's just a salam dua friend meaning someone you only meet to greet and part ways (on daily basis) how amazing that is.... But for quite some time we haven't been allowed to be outside especially children and women to experience the outside world so we see lot of children and women lacking social skills and having self esteem issues because they weren't allowed to grow and fulfill their developmental needs. No wonder why our nation lack leaders...!

So I want to ask you now, what else have you been able to observe in public spaces around you and what other people behaviors teach you about the crisis in your country? What sort of crisis are there? I have only mentioned 5 but there are many that I have observed. What solution do you have to mitigate these crisis? Do you think if we reclaim our public spaces being a responsible citizen and being a better human (not just supposing that we are but becoming one) and set new examples rather good examples of how a society should behave and be and inspire our children as responsible adults and showcase good moral values, can that be a sensible step to transform our communities and the behaviors around us? There is nothing to prove to anyone just to be... Just to live a healthy life for ourselves. Just a lifestyle that's not only good for me or you but for everyone... Do you think that it can be done? Do you want to do it? Share your feedback. I am here listening.

Photo: Liubov Ilchuk/Unsplash

‘It is not the right moment to try and understand Russians.’ Sophia Andrukhovych In Dialogue With Orhan Pamuk

In order to comprehend the events of recent days, PEN Ukraine has launched a series of conversations entitled #DialoguesOnWar. On July 8, Sophia Andrukhovych, Ukrainian author and translator, held a conversation with Orhan Pamuk, author and Nobel Prize winner in Literature.

This conversation is supported by the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine.

In order to comprehend the events of recent days, PEN Ukraine has launched a series of conversations entitled #DialoguesOnWar. On July 8, Sophia Andrukhovych, Ukrainian author and translator, held a conversation with Orhan Pamuk, author and Nobel Prize winner in Literature.

This conversation is supported by the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine.

By PEN Ukraine with Sophia Andrukhovych and Orhan Pamuk

Photo: Pavel Kononenko/Unsplash

Orhan Pamuk: Hello, I am very pleased to have this conversation. I am here, in my summerhouse, in Istanbul, away from the town. I want to ask you, Sofia, where are you now? Where were you when the war started and what were you doing at that moment?

Sophia Andrukhovych: Hello Orhan, hello everyone, thank you so much for having me. I was living in Kyiv when the war started. I have been for 17 years. I was born in Ivano-Frankivsk, a little town in the western part of Ukraine. And after the first week of the war, my family and I fled there. It all started when I woke up at 5 in the morning. I never wake up that early. I had this awful feeling I could not explain. I was just lying in my bed listening to silence. Then suddenly I heard an explosion and felt trembling.

Orhan Pamuk: Were you expecting something like this to happen when you went to sleep that night?

Sophia Andrukhovych: Yes. We were warned by the American and British governments. We knew that Russian forces were near our border. In a way, we were somewhat prepared, but you can never really prepare for something like this. I woke my husband up and told him that the war had started. Then immediately I thought, is our daughter going to school that day? Probably it was my conscience trying to make everything normal. Only then I understood: nothing will be the same anymore.

Orhan Pamuk: Did you immediately wake your daughter up?

Sophia Andrukhovych: Yes, I started packing things because we were hoping to flee on the first day. That’s when she woke up, and I tried not to scare her and to explain what was happening. She’s 14, so she was aware of the news.

Orhan Pamuk: And the explosions were continuing?

Sophia Andrukhovych: Yes, every 20 minutes or so. Although my memory may have changed a little. The sirens were on. We were told to hide in the bomb shelters because staying at our flat was dangerous. One of the shelters was the Kyiv Metro. I think you have been to Kyiv and have seen it yourselves before.

Orhan Pamuk: Yes, how far away was the subway station from you?

Sophia Andrukhovych: About 5 minutes. It was so unrealistic. This huge underground space is filled with hundreds of people. They were sitting so close to each other, with their cats and dogs. They were shocked. However, when I started to watch the people, I was surprised to notice how calm they were. They came with their suitcases, bags, and chairs, but they were very composed.

Orhan Pamuk: Back then, how long did you think the war would last?

Sophia Andrukhovych: I had somewhat naïve thoughts. I could not imagine that now, in our times, something like this could happen. When it started, I hoped that the world would not allow this. I hoped that other countries would interfere and influence the situation in some way. I hoped such an atrocity would be stopped. Now I see how naïve I was.

Orhan Pamuk: What did your husband say? If you were writing a novel set in that particular moment, what would the conversation between the two of you be like?

Sophia Andrukhovych: I asked my husband’s opinion on the situation. We talked about the Ukrainian troops, the people who volunteered and joined the Armed Forces, who took up arms to fight for our country. We also talked about what we had to do to stay alive. Those first days were mainly about surviving.

Orhan Pamuk: How long did you stay in the subway station that day?

Sophia Andrukhovych: About 6 hours. It became very tiring and depressing. We saw elderly people, sick people, and little crying children. So we decided to return home.

Orhan Pamuk: Sorry to ask, but were there toilets or food in the Kyiv Metro?

Sophia Andrukhovych: There was one toilet for this huge crowd of people. So, it was not very convenient. Every family had its food. But from the very beginning the desire to help each other, to make this situation easier, was obvious. Sharing food and helping people next to you with medicines felt like saving lives. It started then, and it is still going on, this willingness to help and to support.

Orhan Pamuk: It is so great to hear about this solidarity. But were there people who were acting egotistically, on their own? Sorry for this question.

Sophia Andrukhovych: I am sure there were, but I have not met them. I saw only kindness.

Orhan Pamuk: What did you learn about humanity throughout this process?

Sophia Andrukhovych: I have learned that humanity is kinder than I imagined it to be. But at the same time, I saw these horrible things going on: Russians killing, raping Ukrainians, ruining our cities. Of course, this radicalises Ukrainians. People cannot simply be kind when something like this is going on. We become tougher. We see everything in black and white. It is a survival mechanism working like that. When you are in danger, when it comes to life and death questions, you cannot perceive shades.

Orhan Pamuk: You are telling us very interesting things. Are you keeping a diary?

Sophia Andrukhovych: I am writing essays, and those essays are my diary. I did it every couple of weeks and I noticed that every essay was like a chronicle of what was happening to me.

Orhan Pamuk: During this whole time, including the moment just before the war, did you regret not doing something?

Sophia Andrukhovych: I do not think I have regrets about the time before the war. But, possibly, I have regrets about not doing enough during it. At the same time, I know it has to do with the radicalisation I mentioned before. You always demand from yourself to be the best, to be like the people you see and read about in the media. You constantly feel like you are not enough, and this is a humbling experience. You have to remind yourself every day that you can do only what you are capable of doing.

Orhan Pamuk: I understand. Besides the aggressive Russian army, what are you most angry about?

Sophia Andrukhovych: Maybe I am angry at the Ukrainian government for not doing enough before the war. They were warned about the situation and they could organise things more efficiently to save more human lives. But I also understand that these people were also experiencing something like this for the very first time. So, even though I am angry, at the same time I understand that it could be worse. They do what they can.

Orhan Pamuk: Do you have any family members or friends who died in the war?

Sophia Andrukhovych: Fortunately, I do not. I know many people who lost their homes, fled the country and were injured. But no one among my relatives and friends was killed. Except for Roman Ratushnyi, about whom you have probably heard. He was the son of my friend, a Ukrainian writer Svitlana Povalyaeva. I have known him since he was a kid.

Orhan Pamuk: Are you a different person now? Or are you the same person who has been through a radical experience?

Sophia Andrukhovych: I would not say I am different. It is rather a question of trauma. I am fortunate not to be traumatised in a way that would make me a different person. I am the same person, just with a much deeper experience and a constant feeling of death being close to me, to my loved ones, to everyone in Ukraine. Our life will never be the same anymore. Ever.

Orhan Pamuk: What is the side of your life that you miss the most?

Sophia Andrukhovych: I miss not having innocent dreams about the future anymore. I am sorry Ukrainians are so traumatised now that I do not know how we will manage this trauma. How much work do we have to do to overcome it and how long will this work take. Children who lost their parents and vice versa. People who lost their homes. Raped women and children. I cannot imagine how we, as a society, can cope with it. Although I believe that we have to do it eventually. There is no other choice.

Orhan Pamuk: What do you dream of most now?

Sophia Andrukhovych: I dream for the war to end.

Orhan Pamuk: Of course. And after it does, what do you dream would happen?

Sophia Andrukhovych: I suppose the best thing would be to see that my country is not endangered anymore. And to see that all of us have embraced our Ukrainian identity. This war is against our identity. It has been going on for hundreds of years. It has traumatised us before, and we have not worked through those traumas. Trauma is an awful thing, it does not allow us to live our lives fully. But at the same time, it can bring a new realisation of who you are, a new understanding of this particular moment in your life, and the things you cherish.

Orhan Pamuk: How come Russians are seemingly ignoring this war?

Sophia Andrukhovych: Russians see Ukrainians as second-class, lower-quality Russians. When they started this war, ironically, they made many Ukrainians realise that we are not the same. We do not want to be with them. We are our own people. While this war is an unnatural and awful thing, it made many of us realise, on a deeper level, our path. It strengthened our identity. I know for sure that for many Ukrainians at the moment it is better to die knowing who you are than to be with Russia.

Orhan Pamuk: Do you have strong negative feelings against the Russian people?

Sophia Andrukhovych: I do. I think it is natural. It is not the right moment to try and understand Russians. For me, it is way more important to analyse processes that are going on within ourselves, and in our society.

Orhan Pamuk: Who do you blame the most in the international community? Who is the most cynical? We are addressing writers, intellectuals, and journalists.

Sophia Andrukhovych: I would rather not name the exact people whom I blame. But the support we have now is not enough. The war is going on, and we cannot see the end of it. But at the same time, I realise that the world is united around Ukraine. I see this huge sincere help, and I feel it.

When the war started, the Russians wanted to destroy us completely. If Ukrainians did not want to be close to Russia, it was better for them not to exist at all. But it did not work the way the Russians wanted it to.

The huge interest in Ukraine brought by the full-scale invasion is very important. Everyone who has some kind of influence should try and learn more about us. To translate Ukrainian authors, to find out more about our history, to understand us better. The main thing is that we are noticed now. I hope this interest will only grow in the future.

Orhan Pamuk: I am shocked that such a war, just like WWII, is happening so close by. Due to this war, I now observe the Ukrainianness of the Ukrainian people. Besides the war, the nation is flourishing.

Edited by Cammie McAtee

Photo: Nick Tsybenko/Unsplash

Neighborhood Revitalization Without Gentrification

“Most communities don't think about gentrification until it is too late. The best time to counter gentrification is when it is still unimaginable, and the real estate is still affordable. So, in addition to working on immediate projects and issues to make their neighborhood more livable, the residents need to create a plan for keeping it affordable. Here are some thoughts on what might be included in such a plan taking an ABCD approach.” Community activator, Jim Diers, explores the collective power of neighborhoods.

“Most communities don't think about gentrification until it is too late. The best time to counter gentrification is when it is still unimaginable, and the real estate is still affordable. So, in addition to working on immediate projects and issues to make their neighborhood more livable, the residents need to create a plan for keeping it affordable. Here are some thoughts on what might be included in such a plan taking an ABCD approach.” Community activator, Jim Diers, explores the collective power of neighborhoods.

By Jim Diers, community activator

Photo: Annie Spratt/Unsplash

Where we once dreamed of livable cities and revitalized neighborhoods, we now bemoan gentrification and displacement. As neighborhood conditions have improved, the small businesses and low-income residents, typically people of color, have been driven out. The neighborhood is only livable for those who can afford it.

The blame for gentrification is justifiably placed on institutional racism, young middle-class whites seeking starter homes, corporations attracting highly paid employees from elsewhere, speculative developers, and government programs such as urban renewal and policies promoting growth. But we fail to recognize that well-meaning neighborhood activists are often unwitting partners in gentrification.

Gentrification is the last thing on their mind as activists work to make their neglected neighborhood a better place. They focus on the immediate challenges of blight and crime. They work hard to paint out graffiti and create public art, clean vacant lots and build community gardens, renovate substandard housing and revitalize the business district, and lobby the government for new and enhanced parks, better transportation, good schools and other public infrastructure that more affluent neighborhoods take for granted. As conditions improve, however, the value of the real estate increases and some of the very people who worked so hard on behalf of their neighborhood can no longer afford to live there. Such is the nature of our market-driven economy.

I believe in taking an Asset-Based Community Development approach to neighborhood revitalization. That involves building on the neighborhood’s strengths and doing so in a way that is community-driven. Every community has abundant resources that it can mobilize to strengthen social capital and improve the neighborhood. These assets include the gifts that every individual has to offer, the collective power of the neighborhood’s many formal and informal associations, and the positive identity that comes with the local history, culture and stories. However, it is important to acknowledge that many communities lack sufficient ownership or control over two assets that are key to preventing displacement – the neighborhood’s real estate and its economy.

Confronting economic challenges in the Canadian Maritime Provinces in the 1930s, Father Moses Coady pronounced: “They will use what they have to secure what they have not.” He helped lead the Antigonish Movement that resulted in producer cooperatives and credit unions. Coady’s dictum still makes good sense for community development work today, especially as we seek to revitalize neighborhoods without gentrifying them.

Neighborhood planning can be a great way to coalesce local associations and tap the knowledge, skills and passions of their members in developing a strategy for gaining greater control over the neighborhood’s real estate and economy. To the extent that there is broad-based participation in the development of the plan and ownership of its vision and recommendations, the neighbors will likely take action to implement their plan and push city hall to do the same.

It’s essential that neighborhoods plan ahead, way ahead. Unfortunately, most communities don’t think about gentrification until it’s too late. The best time to counter gentrification is when it is unimaginable and the real estate is still affordable. So, in addition to working on immediate projects and issues to make their neighborhood more livable, the residents and local businesspeople need to create a plan for keeping it affordable.

A good example is Boston’s Dudley Street neighborhood. The neighbors organized to address the immediate issues of poverty, illegal garbage dumps, and arson for hire. But, even then, when conditions seemed desperate, they were planning for the future. Their goal was to develop a strategy for revitalization without gentrification. That planning effort generated widespread participation and when the document was completed in 1987, a united community was able to convince the mayor to help them implement it. The plan called for the community to be given the power of eminent domain. Normally, eminent domain is a power exercised by government to take control of private land so that it can be redeveloped, typically at the expense of a low-income neighborhood. But the Dudley Street residents were able to use eminent domain to gain control of vacant lots owned by absentee landlords. Then, they secured City funding to redevelop the property through a community land trust, enabling them to provide permanently affordable opportunities for home ownership.

Eminent domain, community land trusts, and land banks are good examples of tools that neighbors can utilize to secure property while it is still affordable. The neighborhood plan might also recommend home sharing, accessory dwelling units, rent control, and property tax reductions or deferrals to keep the existing housing stock affordable and virtual retirement villages enabling elders to stay in their homes. In addition, the plan might urge the city to adopt inclusionary zoning that requires developers to make a percentage of their new housing units affordable.

Ideally, the goal should be more ambitious than keeping low income people in the neighborhood. The plan should also look at ways in which the neighbors can benefit from a more robust local economy by pursuing community-based economic development. The objective is to build a local economy on the strengths of the residents and their neighborhood in a way that contributes to the ongoing welfare of the community. Tools for community-based economic development could include provisions for credit unions, microlending, business incubators, timebanks, and worker or consumer owned cooperatives, and requirements for living wage jobs and the employment of local residents.

Of course, a plan can’t anticipate all the developer proposals and government policies and programs that might impact the neighborhood. That is why John McKnight, co-founder of the Asset Based Community Development Institute, has proposed that plans include a Neighborhood Impact Statement. While this tool could be used to assess all sorts of impacts, it seems particularly well suited to addressing gentrification. Specific and unanticipated developments could be evaluated by the neighbors against a set of broad values and guidelines included in the plan. Such impact statements could also provide a good basis for negotiating community benefit agreements with developers.

Revitalizing neighborhoods without gentrification will always be a challenge in a capitalist economy. Even in Dudley Street, displacement continues to be a challenge. But, unless neighbors organize, plan and take appropriate action at an early stage, gentrification will continue unabated.

Photo: Annie Spratt/Unsplash

Monitoring Violations Of Cultural Rights And Human Rights Of Cultural Figures. Belarus, January-June 2022

Since October 2019, the Belarusian PEN Center has been carrying out a systematic collecting of information on violations of cultural and human rights which impact culture workers. This document includes statistics and an analysis of violations from the first half of 2022. Material has been prepared on the basis of generally available information collected from open sources and direct communications with cultural figures.

Since October 2019, the Belarusian PEN Center has been carrying out a systematic collecting of information on violations of cultural and human rights which impact culture workers. This document includes statistics and an analysis of violations from the first half of 2022. Material has been prepared on the basis of generally available information collected from open sources and direct communications with cultural figures.

By PEN Belarus

Photo: Vadim Velichko/Unsplash

I. MAIN RESULTS

From January to June 2022, experts recorded 699 violations of cultural and human rights that impacted culture workers. Among them are:

529 violations impacting 332 culture workers and others whose general cultural rights were violated;

111 violations impacting 96 organizations and institutions;

41 violations related to objects of cultural or historical heritage and the Belarusian language [on a national level];

*In this document we have also included 18 instances which meet the criteria of our monitoring and are also recognized by the Republic of Belarus as extremist.

The general types of rights violations are as follows:

Illustration: PEN Belarus

The following are also notable:

19 cultural figures were identified as “extremists,” 5 creative initiatives and media with content that is cultural in nature were recognized as “extremist organizations”, and 10 cultural figures were recognized as terrorists.

37 violations of the right of correspondence in penitentiary institutions were recorded.

33 frisk searches on cultural figures and legal persons in the cultural sphere were conducted.

II. POLITICAL PRISONERS — CULTURE WORKERS

According to the human rights organization Viasna, in Belarus there are 1236 political prisoners as of June 30, 2022.

98 cultural figures are among those recognized as political prisoners.

46 of them are serving time in prison colonies:

architect Arciom Takarčuk (serving 3.5 years); artist Uladzislaŭ Makaviecki (2 years); bard and programmer Anatol Chinievič (sentenced to 3.5 years); concert agency director Ivan Kaniavieha (3 years); artist Alaksandr Nurdzinaŭ (4 years of extra labor); documentary filmmaker and blogger Paviel Spiryn (4.5 years); writer and journalist Kaciaryna Andrejeva (Bachvalava) (2 years); artist and animator Ivan Viarbicki (8 years and one month of extra labor); UX/UI designer Dźmitryj Kubaraŭ (7 years of extra labor); artist, former academy of art student Anastasija Mironcava (2 years); drummer Alaksiej Sančuk (6 years of extra labor); culture manager Mia Mitkievič (3 years); writer and social-political Paviel Sieviaryniec (7 years of extra labor); dancers Ihar Jarmolaŭ and Mikalaj Sasieŭ (each 5 years of extra labor); Patron of the arts Viktar Babaryka (14 years of extra labor); actor Siarhiej Volkaŭ (4 years of hard labor); light artist Danila Hančaroŭ (2 years); musician Paviel Larčyk (3 years); poet and publicist Ksienija Syramalot (2.5 years); former students of the aesthetics department at Belarusian State Pedagogical University Jana Orobiejko and Kasia Buďko (each 2.5 years); former student of the Academy of Arts Maryja Kalenik (2.5 years); former student at the architectural department at Belarusian National Technical University Viktoryja Hrankoŭskaja (2.5 years); designer and architect Raścislaŭ Stefanovič (8 years of extra labor); musician, DJ Artur Amiraŭ (3.5 years extra labor); history teacher and social scientist Andrej Piatroŭski (1.5 years); poet, bard and attorney Maksim Znak (10 years of extra labor); musician and cultural project manager Maryja Kaleśnikava (11 years); musician Jaŭhien Piatroŭ (1 year); promoter of history and human rights advocate Taćciana Lasica (2.5 years); author of prison literature and anarcho-activist Mikalaj Dziadok (5 years); musicians Uladzimir Kalač and Nadzieja Kalač (2 years each); promoter of history and blogger Eduard Palčys (13 years of extra labor); author of prison literature and anarcho-activist Ihar Alinievič (20 years of extra labor); musicians Piotr Marčanka, Julija Marčanka (Junickaja) and Anton Šnip (1.5 years each); artist Alieś Puškin (5 years of enhanced regime); litterateur, musician and author of the journal Наша гісторыя (Our history) Andrej Skurko (2.5 years); author of musical projects and typography director Arciom Fiedasienka (4 years); history reconstructor and activist Kim Samusienka (6.5 years); non-fiction author and journalist Alieh Hruździlovič (1.5 years); author of texts in journals «Наша гісторыя» and «Arche» Andrej Akuška (2.5 years); philology and former Russian and Belarusian literature and language professor Mikalaj Isajenka (1.5 years); musician and activist Siarhiej Sparyš (6 years of enhanced regime); non-fiction internet author and blogger Paviel Vinahradaŭ (5 years).

5 cultural figures are serving time by means of «chemistry»:

Poet and director Ihnat Sidorčyk (sentenced to 3 years); designer Maksim Taćcianok (3 years); researcher at the Center for Belarusian Language and Literature Studies at the Academy of Sciences Alaksandr Halkoŭski (1.5 years); director of a web-design studio Hlieb Kojpiš (2 years); cellist Iĺlia Hančaryk (4 years).

46 cultural figures are in pre-trial detention centers run by the MIA and KGB, awaiting either trial or transfer to places of punishment:

Culture manager and blogger Siarhiej Cichanoŭski (since 29.05.2020); culture manager Eduard Babaryka(since 18.06.2020); documentary filmmaker and journalist Ksienija Luckina (since 22.12.2020); poet, journalist, and media manager Andrej Alaksandraŭ (since 12.01.2021); poet and member of the Union of Polish People Andrej Pačobut (since 25.03.2021); literary figure and translator Aliaksandr Fiaduta (since 12.04.2021); author, editor, and political scientist Valeryja Kaściuhova (since 30.06.2021); literary theorist, history researcher and human rights activist Aleś Bialacki (since 14.07.2021); street artist and IT-specialist Dźmitryj Padrez (since 15.07.2021); philosopher, methodologist, and publicist Uladzimir Mackievič (since 04.08.2021); former teacher of Belarusian language and literature Ema Stsepulionak (since 29.09.2021); musician Siarhiej Daliviela (since 29.09.2021); librarian Julija Čamlaj (since 30.09.2021); bass guitarist Viktar Katoŭski (since 30.09.2021); musician and violin teacher Aksana Kaśpiarovič (since 30.09.2021); photographer and journalist Hienadź Mažejka (since 01.10.2021); librarian Julija Laptanovič(since 13.10.2021); artist and interior designer Kanstancin Prusaŭ (since 28.10.2021); author and Wikipedia editor Paviel Piernikaŭ (since 03.11.2021); founder of Symbal.by and culture project manager Paviel Bielavus (since 15.11.2021); poet, translator, and journalist Andrej Kuźniečyk (since 25.11.2021); fantasy writer and journalist Siarhiej Sacuk (since 08.12.2021); sound operator Vadzim Dzienisienka (since 28.12.2021); literary figure and activist Aliena Hnaŭk (since 11.01.2022); theater actress Viera Ćvikievič (since 27.01.2022); jeweler and history reenactor Michail Labań (since 17.02.2022); ceramicist Anastasija Malašuk (since 25.02.2022); expelled MSU student in the Germanic-Romance language philology department Danuta Pieradnia(since 28.02.2022); sightseer and traveler Ihar Haluška (since 01.03.2022); musician Kryścina Čarankova (since 22.03.2022); director Dźmitryj Pancialiejka (since 28.03.2022); digital artist Viktar Kulinka (since 30.03.2022); admin of cultural-historical Telegram chanel Rezystans Mikita Śliepianok (since 06.04.2022); creative director of an architecture bureau Kanstancin Vysočyn (since 07.04.2022); musician Aliaksandr Kazakievič (since 09.04.2022); publicist, activist and author of prison literature Źmicier Daškievič (since 23.04.2022); craftsperson and administrator of the space «Alpha-business hub» Aliesia Kurejčyk (since 24.05.2022); commercial director of the theater group Silver screen Aliaksandr Dziemidovič (since 25.05.2022); musician Paviel Bialianaŭ (since 02.06.2022); former producer of event agency KRONA Siarhiej Huń (since 03.06.2022); musician Juryj Hryhier (since 03.06.2022); designer and photographer Dzianis Šaramiećjeŭ (since 14.06.2022); photographer Aliaksandr Kudlovič (since 16.06.2022).

Additionally, due to the repetition of several procedural actions literary person and journalist Kaciaryna Andrejeva (Bachvalava), poet and founder of the literary “Honey Prize” Mikola Papieka, ethnographer and activist Uladzimir Hundar has been transferred to the detention center from their places of imprisonment.

Anžalika Borys, a chairperson of the Union of Polish People in Belarus, was transferred from pre-trial detention to house arrest on March 25, 2022.

Illustration: PEN Belarus.

The sentences of the first half of the year 2022 and all criminal prisoners from cultural figures.

In the first half of 2022 there were 38 court decisions concerning cultural figures:

January 11: sound director Kiryl Saliejeŭ was sentenced to 3 years of ‘chemistry’;

January 14: author of musical projects and typography director Arciom Fiedasienka was sentenced to 4 years in a colony;

January 28: history re-enactor and activist Kim Samusienka was sentenced to 4.5 years in a colony;

February 4: cultural project manager, businessman, and author included in a fairytale collection Aliaksandr Vasilievič was sentenced to 3 years in a colony; scene designer Andrej Ščyhieĺ was sentenced to 2.5 years of ‘chemistry’;

February 7: cellist Iĺlia Hančaryk was sentenced to 4 years of ‘chemistry’; comedian and KVN participant Vasiĺ Kraŭčuk was sentenced to 2 years of ‘home chemistry’;

February 9: artist and interior desiger Kanstancin Prusaŭ was sentenced to 3.5 years in a colony;

March 2: history teacher Artur Ešbajeŭ was sentenced to 3 years of ‘chemistry’;

March 3: non-fiction writer and journalist Alieh Hruździlovič was sentenced to 1.5 years in a colony;

March 15: literary figure, musician and author in the journal «Наша гісторыя» Andrej Skurko was sentenced to 2.5 years in a colony;

March 15: street artist and IT specialist Dźmitryj Padrez was sentenced to 7 years of enhanced regime colony;

March 16: non-fiction author and blogger Paviel Vinahradaŭ was sentenced to 5 years in a colony;

March 23: sound operator Vadzim Dzienisienka was sentenced to 2.5 years in a colony;

March 25: Lyubitelskiy theater actor Kanstancin Šuĺha was sentenced to 3 years of ‘chemistry’;

March 28: director Dźmitryj Pancialiejka was sentenced to 1 year in a colony;

March 30: artist Alieś Puškin was sentenced to 5 years of enhanced regime colony; poet, blogger and producer Uladzislaŭ Savin was sentenced to 8 years of enhanced regime colony;

April 7: author and Wikipedia-editor Paviel Piernikaŭ was sentenced to 2 years in a colony;

April 14: bass guitarist Viktar Katoŭski was sentenced to 3 years in a colony;

April 18: former museum director Juryj Zialievič was sentenced to 1.5 years of ‘home chemistry’;

April 22: musician Vasiĺ Jarmolienka was sentenced to 3 years of ‘chemistry’;

May 5: graphic designer Halina Siemiečka was sentenced to 3 years of ‘home chemistry’;

May 6: theatre actress Viera Ćvikievič was sentenced to 1 year in a colony; former Russian language and literature teacher Anastasija Kucharava was sentenced to 3 years of ‘home chemistry’;

May 20: jeweler and history reenactor Michail Labań was sentenced to 4 years in a colony;

June 1: musical college student Taćciana Barysovič was sentenced to 3 years of ‘chemistry’;

June 7: cultural project manager and sociologist Taćciana Vadalažskaja was sentenced to 2.5 years of ‘chemistry’;

June 8: poet, translator and journalist Andrej Kuźniečyk was sentenced to 6 years in an enhanced regime colony;

June 10: former French teacher Iryna Jaŭmienienka was sentenced to 3 years of ‘chemistry’;

June 15: head editor of newspaper «Novy Čas» Aksana Kolb was sentenced to 2.5 years of ‘chemistry’;

June 17: literary figure and activist Aliena Hnaŭk was sentenced to 3.5 years in a colony; librarian and excursion leader Iryna Kovaĺ was sentenced to 3 years of ‘chemistry’;

June 21: comedian and art director Aliaksandr Talmačoŭ was sentenced to 3 years of ‘home chemistry’;

June 23: philosopher, publicist and methodologist Uladzimir Mackievič was sentenced to 5 years in an enhanced regime colony;

June 24: author, Wikipedia-editor and IT-specialist Mark Biernštejn was sentenced to 3 years of ‘chemistry’;

June 27: Literary figure Aliaksandr Novikaŭ was sentenced to 2 years in a colony;

June 29: musician and violin teacher Aksana Kaśpiarovič was sentenced to 1 year, 2 months in a colony.

Illustration: PEN Belarus.

III. CONDITIONS OF DETENTION

In January-June 2022, there were 66 cases of violations of the conditions of detention of cultural figures in closed institutions of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the KGB. Since the first arrests in mid-2020, “special” detention rules have been in effect for cultural figures detained or convicted under political articles, and this negative “practice” has continued. Solitary confinement cells, pressures from the administration, unhygienic conditions, overcrowded cells, poor-quality medical care or refusal to provide it, deprivation of visits, telephone calls, and a complete or partial ban on correspondence are just some of the ways in which political prisoners are subjected to pressure.

As of June 1, “due to the stabilization of the epidemiological situation”, Minsk Detention center No. 1, Mahilioŭ Prison No. 4, as well as penal colonies stopped collecting “vitamin packages” for prisoners – an extra package each prisoner could receive with a certain set of fruits and vegetables weighing up to 10 kg. It could previously be received once every 30 days. Inmates in the colony can purchase their own necessities in the prison store for a month for two basic units, which is currently 64 rubles (about 23 euros). As for working conditions in places of detention, human rights activists describe them as “slave-like”: the unequipped workplaces, high production standards, inability to choose the preferred type of work, the lack of an employment contract, and “penny” wages leave a lot to be desired. Thereby, the monthly salary of Maksim Znak in the penal colony in February “Vitsba” amounted to 56 kopeks (0.2 euro).

IV. “EXTREMISTS” AND “TERRORISTS” AMONG CULTURAL FIGURES. EXTREMIST FORMATIONS AND MATERIALS

One relatively new and actively developing practice of suppressing dissent is the application of anti-extremist legislation against opponents of the regime. Human rights organizations (Viasna, Human constanta, BAJ, Sova) have noted a trend of extremely broad interpretations of anti-extremism legislation in Belarus since the start of the protests in August 2020. Currently, law enforcement practice is purposefully shaped in such a way that “extremism” in Belarus means participation in peaceful protests, condemnation of violence by making comments on a social network, making emotional remarks about a representative of the authorities, etc.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs of Belarus maintains 3 lists: “List of citizens of the Republic of Belarus, foreign persons or stateless persons involved in an extremist activity,” “List of organizations, legal entities, individual entrepreneurs involved in an extremist activity” (recognized as such without a court decision) and “Republican List of Extremist Materials” (recognized as such by a court decision). Since 2021 all of them are being filled with new names of individuals and organizations with the intention of creating the atmosphere of fear and silence.

Thus, as of July 1, 2022, the list of persons “involved in extremist activity” consists of 426 names, including at least 19 cultural figures: Maksim Znak, Maryja Kalieśnikava, Paviel Sieviaryniec, Artur Amiraŭ, Mikalaj Dziadok, Eduard Paĺčys, Julija Laptanovič, Alieś Puškin, Arciom Fiedasienka (twice on the list), Andrej Ščyhieĺ, Vasiĺ Kraŭčuk, Maksim Šaŭlinski (pardoned back on September 16, 2021), Siarhiej Sparyš, Źmicier Padrez, Mia Mitkievič, Paviel Śpiryn, Ihar Alinievič, Uladzislaŭ Makaviecki and Paviel Piernikaŭ.

71 subjects compile The “List of organizations, formations, individual entrepreneurs involved in extremist activities.” In the first half of 2022, the list includes the Belarusian Council of Culture, an organization that supports Belarusian culture; the Nasha Niva publication (website and social networks, messengers), which has a “Culture” section on its website; the Homel publication Flagshtok (website and Telegram), which covers culture and preservation of historical heritage, etc.; Telegram channels about Belarusian history and culture Historyja and R E Z Y S T A N S.

The Republican list of “extremist materials” contains more than a thousand items. It includes symbols, articles, videos, Telegram and Viber groups, chat rooms and channels, etc. Of those listed for the first half of 2022 alone, we can distinguish 18 items that are related to the sphere of culture or cultural figures (although there would be many more upon closer inspection). In particular, these are media outlets with cultural content: Radio Racyja, Regiyanalnaia Gazeta, Viciebsk Kurier news, media-polesye.by, nadniemnemgrodno.pl, MOST; the YouTube channels Zhizn-malina and Ms. Anne Nittelnacht (a project for Jewish culture research) 4 books by Belarusian authors: Viktar Liachar, The Military History of Belarus. Heroes. Symbols. Colors,” “Belarus at the Crossroads. Collection of articles”, Aĺhierd Bacharevič “The Dogs of Europe” Źmicier Lukašuk, Maksim Harunoŭ “Belarusian National Idea”, and other materials.

“List of Organizations and Individuals Involved in Terrorist Activities” is maintained the Committee for State Security (KGB). Since the fall of 2020, the list has been actively updated with the names of Belarusian citizens and public figures, including cultural figures. Consequently, in the first half of 2022, the list includes Siarhiej Sparyš, Maksim Znak, Maryja Kalieśnikava, Danuta Pieradnia, Aksana Kaśpiarovič, Aliaksiej Parecki, Ivan Viarbicki, Julija Čamlaj, Paviel Vinahradaŭand Siarhiej Cichanoŭski. Ihar Alinievič, Uladzimir Hundar, Paviel Latuška, Anton Matoĺka and Vadzim Hilievič were included until 2022. This adds up to at least 15 people related to the cultural sphere.

V. PERSECUTION FOR AN ANTI-WAR STANCE

On February 24, 2022, the Russian Federation invaded Ukraine. Belarusian authorities supported the actions of the Russian Federation by providing its territory for the deployment of military equipment and contingent. Citizens of Belarus, in turn, have opposed the war and displayed an anti-war stance since the first days of the invasion of Ukraine. Persecution for anti-war statements was most acute in the first months after the outbreak of the war, but detentions are still occurring today. According to the Human Rights Center “Viasna”, on February 27-28, the main day of the referendum on constitutional amendments in Belarus, and the following day, over 1,000 people were detained for saying “no to war” in various cities of the country. Among them were people from the cultural sphere. During the first half of 2022, Belarusian cultural figures who spoke out against the Russian armed invasion were tried for participation in anti-war actions, use of official Ukrainian symbols (having anything with yellow and blue colors), inscriptions in support of Ukraine, materials about the war, anti-war letters sent to state authorities, publications and statements in social networks, etc. One of the most high-profile cases was the 6.5-year imprisonment of Danuta Pieradnia, a student of Romance and Germanic Philology at Kuleshov Moscow State University [expelled], who reposted an anti-war text critical of the actions of Putin and Lukašenka and called to speak out against the war in Ukraine. Danuta Pieradnia is one of the cultural people who were put on the list of “persons involved in terrorist activities.”

VI. PERSECUTION OF THOSE WHO HAVE GONE ABROAD

The tendency to persecute cultural figures disloyal to the authorities, who were forced to leave Belarus but continue to publicly express their opinion about the situation in the country, is gaining momentum. Criminal cases are initiated against them, and their relatives are put under pressure. On May 12, 2022, actions were taken to introduce amendments to the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus, which would make it possible to prosecute citizens who are outside the Republic of Belarus.

To this day, at least 7 criminal cases have already been initiated against the former director of the Kupala Theater, Paviel Latuška. The last one was initiated in February of this year, and it concerns Latuška’s financial activities as Minister of Culture of Belarus in 2012. The pressure was also exerted on him through his daughter, who, according to employees of the Department of Financial Investigations, was also the subject of a criminal investigation and his apartment has been seized as well. In February the Ministry of Internal Affairs put the creators of the satirical duet “Red Green” – songwriter and blogger Andrej Pavuk, and opera singer Marharyta Liaŭčuk on the wanted list, against whom a criminal case had opened earlier for “desecration of the state flag” – based on one of the duet’s videos. The KGB wanted comedian Slava Kamisarenka, who had been living in Russia for a long time, for the “Defamation against the President of the Republic of Belarus”. Representatives of law enforcement agencies were looking for him in Moscow, calling and texting him, earlier they had shown interest in the parents of the artist who were in Belarus. Ihar Kaźmierčak, journalist and owner of the store of national symbols Cudoŭnaja krama at one point has found out that he “had been hiding from the investigation” and was put on the wanted list as well. An unknown person texted Kanstancin Šytaĺ on Telegram and invited him to return to Belarus and come to the regional KGB. It is known for a fact that law enforcement officers searched the domicile, former place of residence or investigated of parents of Andrej Pavuk, Marharyta Liaŭčuk, the owner of the store of national symbols “Admetnasc”, historian Voĺha Vieramiejenka, and documentary filmmaker Maryja Bulavinskaja; furthermore, they ransacked the apartment of mother of civil activist and photographer Anton Motolko. Not only that, Marharyta Liaŭčuk’s parents were detained and tried “for disobedience to the police”, fined 2,240 rubles (about 830 euro) each, and urged to record a video message to their daughter so that she would “stop engaging in politics.”

VII. LIQUIDATION OF NON-COMMERCIAL ORGANIZATIONS IN THE CULTURAL SPHERE

In the monitoring of the liquidation of Belarusian non-profit organizations [NPOs] conducted by Lawtrend together with the OEEC, as of early July 2022, the list contains more than 500 organizations subjected to forced liquidation since 2021. Of these, since the beginning of 2022, more than 170 NPOs in Belarus have been liquidated, most of which are Minsk-based organizations. At least 32 organizations from this list were directly related to the activities in the sphere of culture. The oldest NPOs [founded in the mid-1990s], such as Polish Cultural Society in Lidčyna, Club of Polish Folk Traditions, and Public Association of Former Young Prisoners of Nazi Concentration Camps in Hrodna region; Jewish Cultural Center of Polack and Viciebsk Musical Society in Viciebsk region; Belarusian Association of Architectural Students, Jewish Educational Initiative, and Polish Scientific Society in Minsk region.

As a result of the unfavorable socio-political situation in the country or pressure from the authorities, the list of NPOs that have decided to spontaneously dissolve is expanding. As of early July, Lawtrend monitored 336 organizations. 99 of them filed petitions for self-dissolution during the first half of 2022. 40% of the self-dissolved NPOs (40 organizations) were from the Brest region. Most of the organizations were focused on sports and at least 20 – on culture. For instance, the self-liquidation list includes the charity foundation Fortification of Brest, which dealt with the topic of preservation of historical and cultural heritage of the city; Brest cultural and historical public association named after Tadevush Kastsiushka, as well as the Ukrainian Scientific-Pedagogical Union Bereginya, whose leader Viktar Misijuk was detained on March 8 by law enforcement for laying flowers to the monument to Taras Shevchenko on the birthsday of the poet, and in April was a subject to searches.

Furthermore, on January 22, 2022, a new law came into force, according to which there is a responsibility for organizing a public activity or participation in the activity under a patronage of a public association that had been forcefully liquidated. Now anyone involved in such events can be fined, arrested for up to three months, or even imprisoned for up to two years.

VIII. CULTURAL LIFE IN BELARUS: WASHING OUT THE SPHERE AND THE „PURIFYING CULTURAL VISITS”

LITERATURE

As early as the first quarter of 2021 a tendency of pressurization and reprisals against the independent book sector of Belarus began to form: Publishers and their founders, book distributors, and authors. Such forms of pressure as seizure of books during customs clearance, suspension of bank accounts, searches and property confiscation, interrogations, publication of discrediting and defamatory stories and articles in the state media, removal of books of certain authors and publishers from the shelves of libraries and state bookstores, etc. were exerted on them. Repressions against “the Belarusian book” continue for the second year and intensify in the current timeframe.

At the end of March, “due to an urgent need,” the landlord demanded that the publishing house Januškievič vacate the office within three days – and immediately began looking for a new tenant: the owner published an announcement on a rental website that the office space is available.

The Ministry of Information suspended for three months the activity of four independent publishing houses that had been printing books written in Belarusian and by Belarusian authors: Medisont and Goliaths (since April 15), Limarius and Knigosbor (since May 16) for trumped-up reasons.

From April 18 to May 17, 2022, four books by Belarusian authors were recognized as extremist material (see Section IV). Distribution of these books is now criminally punishable.

On May 16, at the opening of a new bookstore named Knihaŭka (owner – publishing house Januškievič) representatives of the state media came and “have criticized” the range of available books, their content, authors, publishers and employees of the bookstore. The same day the store was searched, 200 books were confiscated, 15 of which were sent for ‘an examination’ to determine whether they had signs of extremism, whereas Andrej Januškievič, the founder of the publishing house, and the literature reviewer Nasta Karnackaja, an employee of the store, were arrested and spent 28 and 23 days in jail respectively, on trumped-up administrative charges. [Symbolically, a month later, on June 15, a pro-governmental store called Book Club of Writers was ceremoniously opened.]

The practice of discrediting writers disloyal to the authorities (as well as historians, artists, filmmakers, public organizations, etc.) has “proven itself” at the state level and is a full-scale “campaign” in the state media. Over time, state propagandists “went into the field” (as in the case of the Knihaŭka store, for example, or the Art-Minsk painting exhibition): in the course of their “purifying cultural visits” they completely distort the truth and slander certain [disloyal to the regime] authors and their works, which is then followed by administrative penalties and a ban on the distribution of the literature. At some point the propagandists were joined by pro-government bloggers-activists who would roam around the city and visit numerous exhibitions and bookstores in search of ideologically “harmful” materials.

For example, after an appeal by an activist, the OZ Books stores located in Trinity and Nioman shopping centers had to move “Summer in a Pioneer Tie” and other books touching on the LGBT topics to the storage rooms and the managements of the bookstore and the Trinity shopping center were invited for a “preventive conversation of a proactive nature”. Later, in Hrodna the Green store had to take off sale the following books: “Myths about Belarus” by Vadzim Dzieružynski and “Welcome to Belarus” by Alieś Hutoŭskahi. They were released by the same publishing house as the books written by Viktar Liachar of which one is considered extremist.

VISUAL ARTS

Pro-government activists Aliena Sidarovič in Minsk and Voĺha Bondarava in Hrodna control both the cultural landscape of the book market and art exhibitions. The letters they send to the departments of culture of the Minsk and Hrodna City Executive Committees result in taking down works of both recognized and young authors.

After the claim about the alleged distribution of pornography at the exhibition “Troubling Suitcase” (“Тревожный чемоданчик”) held from 10.12.2021 to 10.02.2022 in the gallery of the Union of Designers, the culturological examination of the art-object “Till death do us part” (“Пока смерть не разлучит нас”) by the artist Hanna Silivončyk was appointed. As a result, proceedings began not only against the exhibition itself, but also against the public association as a whole.

In March the personal exhibitions of Hryhoriy Ivanau “The Time of Screens” (“Час экранаў”) and Siarhei Hrynevich “Demography” (“Дэмаграфія”) in Palace of Arts in Minsk were closed before the schedule.

On April 29, the sculpture exhibition “SCULPTURE” was held for 4 hours in the gallery “400 squares” in Hrodna. The Hrodnian ideologists proposed to remove some works as a condition for the further functioning of the exhibition, to which the project curator Ivan Arcimovič and gallery owners did not agree, considering it wrong to exclude the works of individual authors “for absolutely far-fetched reasons”. The Belarusian Union of Artists, the members of which are the participants of the group exhibition, tried to defend the project and was ready to create an expert commission of famous art historians and sculptors, which was not supported by the administration of Hrodna. Thus, the exhibition with the works of 17 sculptors was closed immediately after the opening.

On May 12, the annual “Art-Minsk” exhibition opened at the Palace of Arts, announcing an exhibition of 550 works by 240 contemporary Belarusian authors. However, dozens of artists (according to unconfirmed information, this amounts to “over 40”) could not take part in it, and some had to withdraw their original works: a so-called “black list” was issued “from above,” while the content and quality of the works on display did not play any role at all. The PEN monitoring contains information about 19 authors who were censored in one way or another because of their “unreliability”.

On June 28, Irina Malukalova was one of the three participants involved in the art project that had taken place in Factory space in Minsk which she later described as “the fastest exhibition of my life.” The exhibit about criticism of creative work “This is a diagnosis” (“Это диагноз”) had lasted for several hours and then was promptly taken down. The reasons for such a rapid removal remain unknown.

ART-SQUARES AND FESTIVALS

After the events of 2020, the cultural sphere is largely paralyzed: many musicians, theater artists, promoters, DJs and other people of creative professions have left the country (unfortunately, there are no real statistics on the number of people who have emigrated). Many of interdisciplinary cultural venues have closed. During the first half of 2022 the decision about discontinuation of work has been announced by the cultural center Korpus (June) and Lo-Fi Social Club (March).

It is known that in the first six months of 2022 Minsk cultural center Korpus (June) and Lo-Fi Social Club (March) ceased their work and event space Miesca was forced to close (April). Since mid-May activities of Minsk music club Bruges have been suspended, the doors of which were sealed after one of the complex inspections of the building’s owner. The playbill of the theater The Territory of Musical, which at the beginning of the year twice failed to show the performance “Figaro” for reasons beyond the control of the theater, is not updated. In May, after the notorious incident with the closure of the exhibition of modern sculpture, the shopping center Trinity did not prolong the lease agreement.

This year there are significantly fewer traditional summer festivals and cultural events announced, which had been organized by private initiatives. Inter alia, Ukrainian and foreign artists refuse to tour in Belarus because of the war in Ukraine. Also, many Belarusian musicians have left their country or have no chance of getting a touring certificate for a concert. “Those things that worked like clockwork in 2019 (permits were issued, concerts were held, everything was moving), after 2020 by the confluence of all circumstances it turned out to be completely different. Now there are no criteria and notions of what can and what cannot be done.”

IX. GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS IN THE CULTURE SPHERE: DEBELARUSIZATION AND RUSSIFICATION

The problem of the consistent displacement of everything that is nationally oriented in culture, education, everyday life, and other spheres of Belarus is perennial and complex. It would not be possible to cover the topic in this research, however, it is of paramount importance to identify and note what is happening in the domestic policy of Belarus as a practice of debelarusization and russification – using examples of the first half of 2022.

DEBELARUSIZATION

In detention facilities, Belarusian-speaking detainees and prisoners are ordered to “speak in a normal language” – Russian. According to historian and publicist Alieś Biely, “people with ‘non-Russian’ cultural affinities are being systematically forced out of all educational and cultural institutions”. An increasing number of inscriptions with names of streets and places of interest in Belarusian cities are being changed from Belarusian to Russian. Belarusian authors disloyal to the authorities are discredited by pro-government propagandists and activists.

After some time, it became apparent that in November 2021 the publishing house “Belarusian Encyclopedia of Piatruś Broŭka”, founded in January 1967, ceased to exist. The formal reason is incorporation into the publishing house “Belarus”. In fact, it is liquidation of a specialized publishing house. The company website notes that this publishing house “specialized in the production of universal, regional and subject encyclopedias, all sorts of reference books and dictionaries, educational, children, and popular scientific literature. Furthermore, elite publications, unique photobooks, and anniversary editions were also issued there. Journalist and literary critic Siarhiej Dubaviec described the incident as an act of “denationalization” and the publishing house BelEN as “the intellectual center of the Belarusian identity” and “a powerful state institute”, which had been dying for a long time, and now it finally has happened.

Uladzimir Savickai, ex-managing director of the Belarusian Theatre for Young Audience had been dismissed in January of this year and replaced by actress Viera Paliakova, who is also wife of the minister of foreign affairs of Belarus. Paliakova announced that the theater would give up staging exclusively in Belarusian – which used to distinguish the playhouse as one of the few professional theaters with only Belarusian-language performances [only 6 theaters in Belarus out of a total of 29]. In June, the premiere of the play based on Vasiĺ Bykaŭ’s story “The Alpine Ballad”, originally written in Belarusian, took place. Thus, there is one less Belarusian-language theater in the country.

On June 27, by Lukašenka’s order, the former chairman of the pro-governmental Union of Writers of Belarus (2005-2022) Mikalaj Čarhiniec was awarded the title of People’s Writer of Belarus. After 27 years [the last time it was awarded was in 1995] and for the first time in its history, the award was given to a writer who had not written a single work in the Belarusian language, an author of detective stories and militarized literature; a person under whom the so-called “black lists” of writers appeared.

There are only four schools in Belarus teaching in the language of national minorities. The transfer of two Polish (Hrodna and Vaŭkavysk) and two Lithuanian (Pieliask and Rymdziunsk) schools to Russian language starting next school year is further pressure on Polish and Lithuanian minorities and continuation of the russification. Such decision of the Belarusian authorities is exclusively discriminatory against the rights of national minorities.

THE PROMOTION OF A “RUSSIAN WORLD” IDEOLOGY

On February 19, a gala concert dedicated to “national unity” was held in Minsk. On Sunday, June 11, there was another concert in Minsk, but this time in celebration of Russia Day [a state holiday celebrated in Russia on June 12 since 1992], which was sponsored by Russian state corporations. Events dedicated to this date were also held in other cities. At the Night of Museums in the National History Museum the program included the performance of Cossack songs and at the meetings with a Russian actor Minister of Culture Anatoĺ Markievič discusses the idea of cooperation between “two brotherly nations” in the sphere of culture. Russian flags are increasingly seen on the streets of Belarusian cities, at official institutions of the country and during public holidays. For instance, they were hoisted in flagpoles along a part of Victors Avenue in Minsk just before the Day of Unity of the nations of Belarus and Russia (in previous years they were not put up there), raised on the station building in Orša, were marked in Homiel and a number of other places. In Hrodna, the monument to Chapayev [a Russian historical character], dismantled in April 2019, “returned”; now it will be next to a military unit

The “Russian House” representative office of “Rossotrudnichestvo” actively operates in the territory of Belarus. The organization supports programs for kindergartens, schools and universities, actively collaborates (as can be seen from announcements of events in social networks) with schoolchildren, applicants and students, often acts as a partner of educational, cultural and entertainment events, holds exhibitions, cinema clubs, master classes, tournaments and conferences.

For example, the “Russian House” participated in the opening of an art exhibition marking the 75th anniversary of the Hliebaŭ Art College in Minsk. On June 2, the Center for Russian Language, History and Culture has opened in Polack with assistance of the “Russian House”. The goal of the center is to popularize Russian language, culture and traditions. On the page of the representation office it is mentioned that such centers already operate at the Belarusian State Univeristy (Minsk), the Belarusian-Russian Univeristy (Mahilioŭ) and other Belarusian higher educational establishments. One of the implemented programs – “Hello, Russia! – “cultural and educational trips for young compatriots to historical places of the Russian Federation,” according to the website.

On June 23, a joint Russian-Belarusian group was created to investigate criminal cases of genocide – the Prosecutor-General of Belarus Andrej Švied and Chairman of the Russian Investigative Committee Aliaksandr Bastrykin signed a resolution to collectively investigate “the circumstances surrounding the atrocities of the fascists.” At an Independence Day event in Belarus, Lukašenka officially expressed support for Russia in the context of military action against Ukraine, and Slavianski Bazar, the main state music festival to be held in July, invited artists who either spoke out in favor of the war or who did not speak out publicly against it.

X. GOVERNMENTAL AND POLITICAL TRENDS IN THE CULTURAL SPHERE

Suppression of all forms of dissent.

The severely expanded interpretation of extremism as a method of suppressing the freedoms of speech, assembly, and association. The purposeful formation of law enforcement practices with unclear criteria and the criminalization of public and civic engagement.. The practice is formed “behind closed doors” – in closed court hearings, which does not give the public any clear understanding of what actions and under what circumstances are considered crimes. This creates grounds for investigators, prosecutions, and courts to expand the interpretation of the law in the future.

Monopolization of cultural activities by the government. Thus, according to the decree of June 22, 2022, a register of the organizers of cultural and entertainment events is being formed in Belarus. The Ministry of Culture or a legal entity authorized by it will consider the documents for inclusion in the database and maintain the register. Organizers, eligible for inclusion, but not included in this list, will not be able to carry out cultural and entertainment events. In practice, this means that only state or regime-loyal organizers will be allowed to hold events. The decree came into force on August 1, 2022.

Debelarusization of Belarus through the means of Russification and promotion of the concept of the “Russian world”.

The Sovietization and militarization of routine.

The reduction of “cultural diversity” to the “cooperation of two fraternal nations” [Belarusians and Russians] and the suppression of the culture of Polish and Lithuanian national minorities.

The systematic implementation of the program within the framework of the Year of Historical Memory (2022), the purpose of which is to “develop the objective perception of the historical past of the Belarusian society…” One of the egregious events that took place last month – the destruction of the graves of The Home Army soldiers in Hrodna region – is a continuation of the erasure of historical memory about the underground military organization from The Second World War that opposed the German occupation. The question of historical memory and what is happening in this area requires additional attention and investigation.

Making foreign policy decisions that contribute to the cancel culture phenomenon – cases of boycotts of Belarusian cultural products and their authors.

You can support the work of PEN Belarus at their Patreon site.

Five Ways To Address Objections About Shopping Local

Deb Brown and SaveYour.Town highlight five opportunities for local residents and businesses to help create change and share a new mindset on how to think about community.

Deb Brown and SaveYour.Town highlight five opportunities for local residents and businesses to help create change and share a new mindset on how to think about community.

By Deb Brown and SaveYour.Town

Photo: Andrea De Santis/Unsplash

I’ve heard business owners say things like “in this economic climate, it’s hard to get new customers” and “no one has any money to spend, we can’t afford to use new ways to advertise”.

I’ve heard customers say “they never do anything different” and “why should I shop local? I can get a better deal at the big box store?”

These comments are opportunities for local residents and businesses to help create change and share a new mindset on how we think about our community.

Here’s 5 things to consider:

1. Stop saying “in this economic climate” – people are still shopping, traveling, and talking about businesses/places they visit. Start looking at what people want. Where we live, there are more day travelers coming from around the state. What can you provide for them?

2. Don’t spend other people’s money. In other words – don’t prejudge people. You really don’t know what their priorities are and how they want to spend their money. People do have money to spend.

3. New ways to advertise don’t always cost money. They do cost time. Facebook, twitter, LinkedIn, blogging can all be done for no cost or almost no cost. You do need to spend time on it to be effective. You wouldn’t just put up a billboard and expect people to flock to your store either. People need to see something 7 times before it sinks in!

4. If you’re not doing anything different, you’re become stale. Rearrange your store, change the windows, use new ads in the paper and on the radio – give people a reason to come visit you.

5. The big box store helps put small, local businesses out of business. Most of your dollars spent at big box stores don’t make their way back to your county/town. 57 cents out of every dollar leaves your community. 66 cents of every dollar spent in your local small businesses, stays local. Local businesses also know you, give much better customer service as a rule, hire people from your neighborhood, pay local taxes, and live where you live.

Photo: Markus Winkler/Unsplash

How Local Leaders And Officials Can Become Venture Capitalists Of New Ideas

“How can you protect your community from failure while being open to new ideas?” Becky McCray and SaveYour.Town answer an essential question.